A former school board member announced to the Kansas House K-12 budget committee on Monday that she changed her mind about education savings accounts (ESAs) and school choice initiatives.

Joy Eakins, a former Wichita School District Board member, testified in favor of HB 2119 on Monday. The legislation, known as the Student Empowerment Act, would allow parents to withdraw their children from a public school and receive state funds into a government-funded savings account to be used for education. The state would fund the account equal to the amount of base state aid per pupil, currently $4,659. Parents could use the funds for private school tuition or other educational endeavors.

“In 2013, I staunchly opposed measures like this bill,” Joy Eakins, a former Wichita School District board member told the committee on Monday. “I believed we could bring change from the inside and fix these issues for our most vulnerable students. But now I’m here today asking you to pass this bill because I got a good look at the inside of the system.”

Eakins saw firsthand problems in public schools

Eakins got her first glance when she visited a classroom in 2011 with an at-risk child her husband was mentoring. She realized “the system just saw this bright young man, in their own words, as someone who was doomed to fail. It was heartbreaking.”

She received a sharper look after she won her USD 259 school board election.

“In the four and a half years I sat on the board in Wichita, we had one meeting where student achievement data was brought for discussion,” she said.

She told the House committee that the district reported the results were encouraging. However, the results showed that in five of the Wichita School District high schools, one in two students tested below grade level in math.

“That was the last time we discussed state testing results in a meeting,” she said. “Instead, the board talked about the new school facilities we should build, how to maximize the mill levy authority on our citizens, lawsuits against the state for more money, and balancing the budget by cutting programs for at-risk high school students to save SEIU labor contracts.”

Student achievement is much lower than parents have been led to believe, and have gotten worse over time.

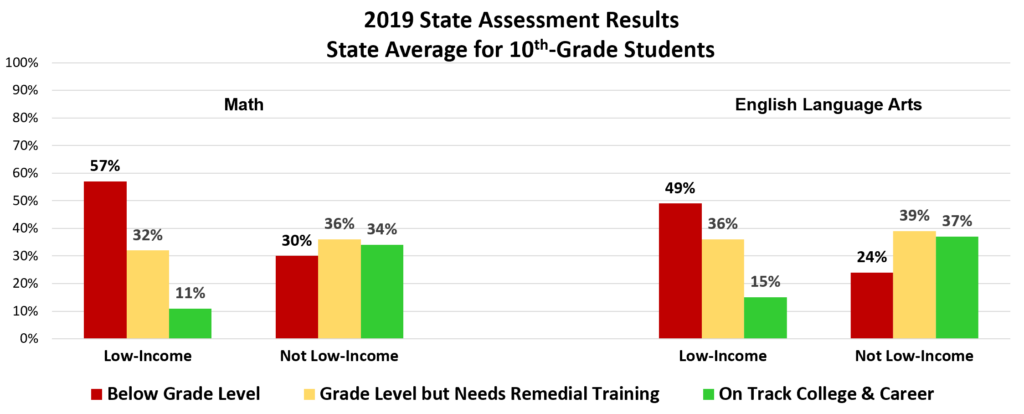

The 2019 state assessment shows 57% of low-income students in the 10th-grade are below grade level in math; 32% are considered at grade level but still need remedial training, and only 11% are on track for college and career. 10th-graders who are not low-income do better but still low, with roughly one-third of students in each category. Results for English Language Arts are similar.

Many school districts have more 10th-graders below grade level than are on track for college and career.

Association of school boards opposes the proposal

The Kansas Association of School Boards opposes the legislation, saying the proposal would take funding away from public schools, too many students would be eligible, and it would create a two-tier school system.

Mark Tallman, a lobbyist for the Kansas Association of School Boards, said under the proposal, all students would be eligible to participate. The legislation makes eligible students on free and reduced-price lunches, students who receive at-risk services from the school district, and students who have been in remote and hybrid learning modes.

“If this went immediately into effect, every kid would qualify,” Tallman said.

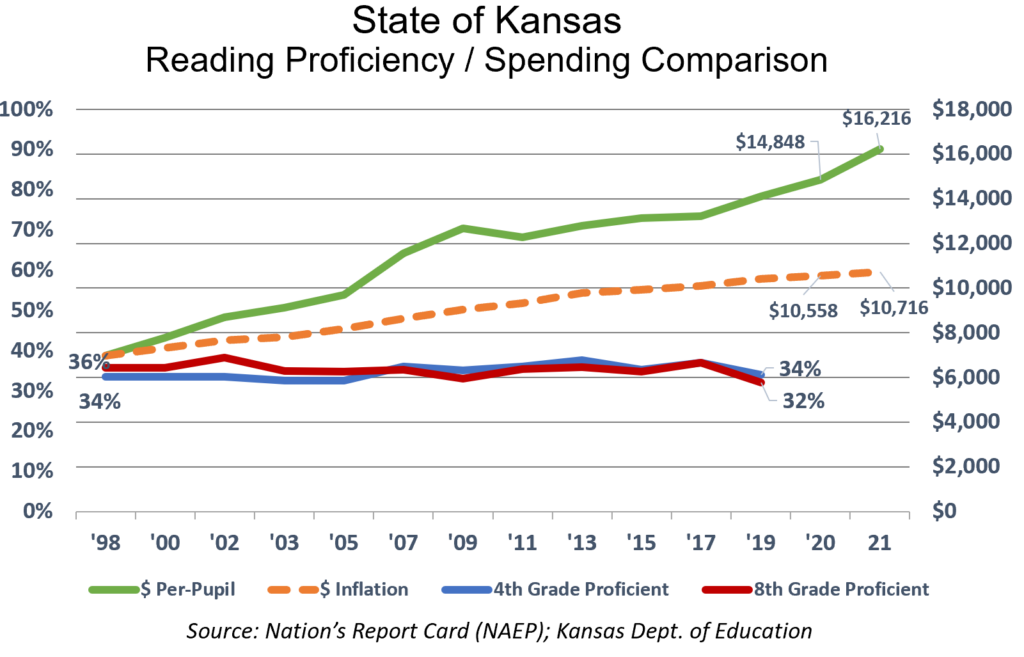

Kansas funds education using a complex formula based on student enrollment. This year, schools receive $4,569 per student in base state aid. Each student is weighted, however, and schools receive additional funding for certain students. For example, students who live a certain distance from the school building, students on free-and-reduced lunch programs, and students who utilize school special needs services receive additional funding. In total, taxpayers provide more than $16,000 per student to public schools. Under the legislative proposal, the state would provide the base state aid funding into an individual student account, currently at $4,569. The district would retain all of the weighted funding the state provides for three years.

KASB says private schools can be selective

Tallman said private schools reject students who are more costly to educate.

“What we would suggest is those schools that have the highest numbers of kids that aren’t doing well are the districts that have the highest needs for special education,” he said. “…We don’t undermine the environment for kids who won’t have that option.”

Eakins admitted that she is an outlier among current and former school board members. Most, she said, probably agree with the KASB’s position.

“I am in the minority of most school boards. That’s where I stand. I am happy to stand there because frankly, my experience tells me that I need to be on the side of students,” she said.

Parents with options are taking them

An analysis of schools in 33 states by Chalkbeat and the Associated Press revealed that public school enrollment is down 2% nationwide this year. Enrollment typically increases year-over-year. In Kansas, public school enrollment is down 2.86%.

“Parents with options are taking them,” Eakins said. “Wichita public schools have seen declining enrollment for the last five school years.”

James Franko, President of Kansas Policy Institute, said his parents moved from Kansas City, Missouri, to the Blue Valley School District. They made the move to send their children to better schools in the Blue Valley School District.

“The simple truth is that not every family can afford that,” he said. “In fact, too many cannot. They do not have any fundamental choice.”

However, Meghan Hemenway, a Shawnee Mission School District and PTA president, said educating children is a collective responsibility that shouldn’t be decided by people from one demographic. She said removing funding from public schools at this time is insulting.

“I don’t think we should be making changes to public education in the middle of a global pandemic,” she said.

Eakins, however, said poor families have limited options and shouldn’t have to wait for a level playing field

“What about those families?” Eakins asked. “How long do they have to wait for the system to get fixed?”

To Eakins’ point, proficiency on the National Assessment of Educational Progress is lower than it was in 1998, while funding has grown much faster than inflation.

Just as education officials have led parents to believe student achievement is higher than state and national results reflect, they also have a tendency to distort how Kansas compares to other states.

The Sentinel will next examine the veracity of local school boards’ claims on achievement in states with robust school choice programs and other objections to education savings accounts.