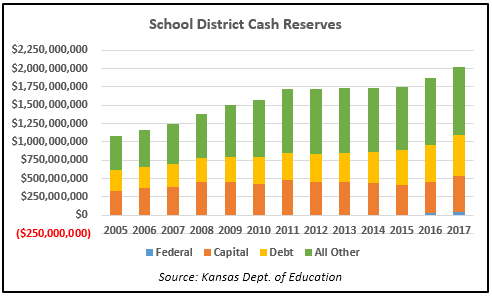

Kansas school districts are sitting on record reserves. According to the Kansas State Department of Education, public schools are sitting on more than $2 billion in reserves. Of that, schools have more than $928 million in operating cash reserves.

“With a few exceptions, operating cash reserve increases are the result of school districts  not spending all of the state and local tax aid they receive to operate schools,” according to the Kansas Policy Institute.

not spending all of the state and local tax aid they receive to operate schools,” according to the Kansas Policy Institute.

Schools received $293 million in additional state funding through FY 2019. The Kansas Supreme Court, however, ruled that funding inadequate. Schools for Fair Funding, a coalition of about 50 Kansas public school districts, and the Kansas State Board of Education say schools need an additional $600 million in funding. Though the Court stopped short of naming a dollar amount, Supreme Court justices side with SFFF and their plaintiff allies on virtually every point in their latest school funding opinion.

Dave Trabert, Kansas Policy Institute President, crunched the numbers on how lawmakers could produce an additional $600 million in state funding for schools. Legislators approved the largest income tax hike in state history last year, so they may not be keen on doing the same again next session. Should they look to rearranging the state budget to meet the school lobby’s demands, they would need to reduce non-K-12 expenditures in the budget by 43 percent. Or, lawmakers could increase the state property tax rate nearly doubling it from 20 mills to 39.5 mills. That would cost the owner of a $200,000 home about $450 more each year. Should lawmakers opt to increase the sales tax rate to raise $600 million, they’d need to increase the rate from 6.5 percent to 7.9 percent. That rate doesn’t include county and city sales taxes, which could push sales tax rates to about 10 percent in many places, creating the highest sales tax rates in the nation. If lawmakers choose to dip into the income tax well for funding, the new marginal income tax rates–if increased uniformly–would be the highest in state history.

Shortly after the 2017 legislative session, Mark Tallman, associate director for the Kansas Association of School Boards, wrote that Kansas’ trajectory of spending is set to outpace inflation. He wrote in a blog post, “It is entirely possible that after (yet another) largest tax increase in state history, Kansas may still face budget challenges, and many Kansans may still feel things are not getting any better for them.”

He recommended school districts start spending down reserves.

“Again, there are many justifiable reasons why districts have increased cash reserves, most notably during the years of state budget turmoil. But after this legislature took steps to finally provide stability for the next two years, districts should consider ways to reasonably invest money in one-time investments, like professional development to improve the educational outcomes,” Tallman wrote.

Could lawmakers claw back from schools money sitting in reserves to meet the Court’s demands?

About half of the state’s school districts lowered their reserves in 2017–136 districts spent down reserves–but 151 public school districts increased their reserves.