The COVID policy metrics being used to make public health decisions and to decide when — or if — to open schools in Kansas’ most populous county are seriously flawed.

That’s the message Kansas Policy Institute CEO Dave Trabert took to the Johnson County Commission this week. His presentation begins about one minute and 45 seconds into the video of the August 20 commission meeting. KPI owns the Sentinel.

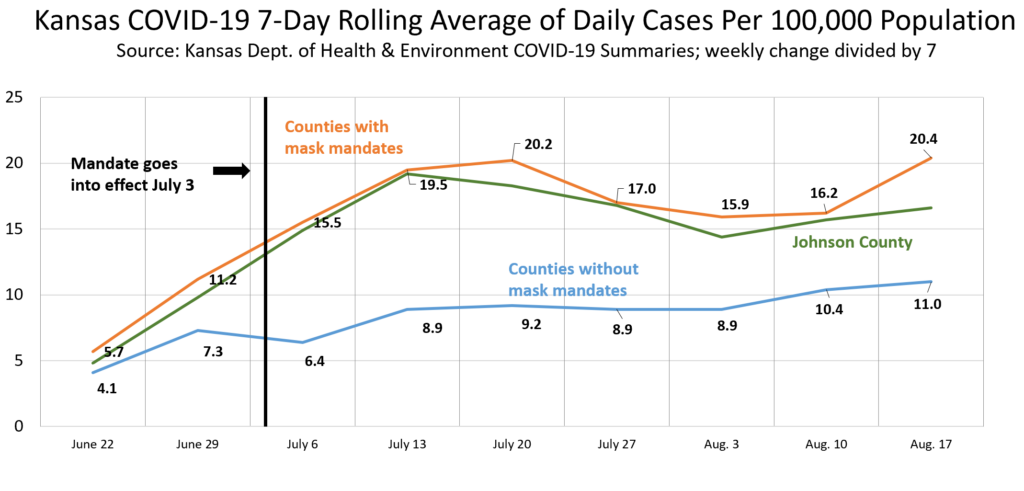

Trabert noted that 16 counties in Kansas — including Johnson County — have implemented a mask mandate, and 89 have not. One might expect those counties that require masks would have fewer cases than those without a mandate (as KDHE Secretary Dr. Lee Norman tried to make people believe), but that hasn’t been the case.

“Both groups of counties have seen an increase … there has been much more of an increase, ironically, in the counties with a mask mandate and the gap between those has grown wider over time,” Trabert said.

Trabert also noted that there’s a great deal of encouraging news about the pandemic in Kansas and Johnson County– which for whatever reason is not reported.

“There’s some really encouraging information … it’s a shame … that media won’t share this encouraging news,” he said. “Because while the focus has been on the number of cases going up…at the same time the hospitalization rate and the mortality rate has been coming down significantly.

“There’s this hyperfocus on one element, but not on the fact that the severity has come down dramatically.”

In Johnson County, the case fatality rate has steadily declined and is sitting at just 1.6 percent, and Trabert noted that was skewed by the fact that most of the fatalities are in senior care facilities. The hospitalization has also been falling, and last week there were only nine new hospitalizations in the county.

Trabert noted that the county keeps moving the goalposts, having shifted from preventing hospitals from being overwhelmed in April (which thankfully never happened) to stopping the July increase in cases, and now to reduce the “positivity rate.”

Trabert asked why the positivity rate is being used as the benchmark for allowing schools to open instead of case severity, which, measured by hospitalization and mortality rates is clearly declining.

Noting that Johnson County has set a five percent positivity rate for allowing full in-person instruction, Trabert asked; “What’s the scientific basis of 5% positivity for in-person school? Why not 8%? Why not 11?”

The rolling positivity rate in Johnson County currently stands at 11.8%. Trabert also pointed out serious flaws in relying on the positivity rate at any level.

“Dr. Christine White a pediatrician with Johnson County Pediatrics, mentioned at a Blue Valley School Board meeting earlier this week that the testing data is skewed,” Trabert said. “The positivity rate is artificially high, because the vast majority, she said, of people being tested have symptoms or known exposure. By comparison, she said, Shawnee Mission medical center tested 7,500 people, pre-op patients, over the last three months and their positivity rate was half of one percent.

“They tested about 700 people who showed up at the ER with a variety of issues and there they found 13 percent were positive.”

He also said there may be an issue with the number of cases being declared positive, saying he knows of one case with Sedgewick county declaring positives in a facility where the first test showed positive, but two subsequent independent tests taken the same day showed negative.

“How much of that is going on across the state?” Trabert asked. “How many people are being counted positive because of antibodies? That means they had the virus at some point, but not now.”

He also noted that the Kansas Department of Health and Environment includes an unknown number of ‘probable’ cases, but refuses to say how many.

Trabert said school gating needs to be based on testing of actual students, not the entire population. He also asked if the county had quantified the serious educational, economic, emotional, nutritional, and physical abuse consequences of not opening schools, which, as the Sentinel previously reported, are severe.

The bottom line, Trabert said, is that the county — and by extension the state — needs to adopt revised risk assessment criteria that balance health issues against devastating economic, educational, and multiple well-being consequences of efforts to mitigate COVID, move to aggressively protect vulnerable residents rather than issue one-size-fits-none orders that are counterproductive, and provide far more data transparency than has heretofore been the case.