According to analysis by one social media site, Wichita is losing employees to out-migration faster than other U.S cities. LinkedIn reports Wichita lost more workers per 10,000 LinkedIn members than any other city in the U.S. in January. It’s a trend that started in August 2018 when LinkedIn, the world’s largest professional network, first reported Wichita topped the list of U.S. cities for out-migration.

LinkedIn calculates migration by analyzing the location data of its members. Jason Watkins, a legislative consultant for the Wichita Chamber of Commerce, isn’t buying the social media site’s analysis.

“One, it’s not scientific, so you have to question the validity of that study,” he says. “And our experience directly contradicts what that study says.”

Wichita Chamber members tell Watkins they have open, high-paying jobs and no one to fill them.

“They are telling us they need workers,” Watkins says. “They’re not saying we need money. They’re not saying they’re getting ready to lay-off people. They’re telling us they need people.”

Wichita’s unemployment rate has continually fallen since July 2018, when the city topped LinkedIn’s list for out-migration. Last summer, the Wichita unemployment rate was 4.3 percent. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported the city’s unemployment rate at 3.2 percent in November.

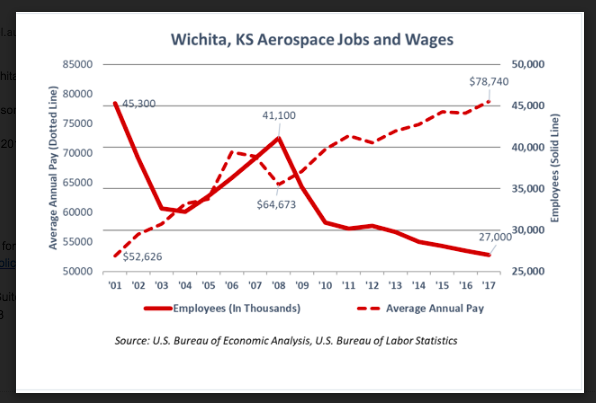

Michael Austin is the director of the Sandlian Center for Entrepreneurial Government at the Kansas Policy Institute, which owns the Sentinel. Austin says one possible reason for LinkedIn’s findings may be traced to the aerospace industry, one of Wichita’s largest industries. Affectionately known as the Air Capital of the World, Wichita’s aerospace industry hemorrhaged manufacturing jobs during the last recession.

“They lost tens of thousands of jobs, and that hasn’t picked back up,” Austin said.

Aerospace’s gross domestic product has increased, but its workforce numbers haven’t rebounded. Wages are up, but the number of employees is down (See chart).

“Many firms are concentrating more on capital, or machinery, instead of having people make widgets,” he said. Austin also notes that Wichita was also affected by falling crop and cattle prices between 2014 and 2016.

Though Watkins disagrees with LinkedIn’s conclusion, he recognizes that Kansas isn’t growing.

“States grow when they have opportunities for citizens to create wealth,” Watkins says. “We’ve been stagnant for a long time, and we’ve got to take an out-of-the-box approach to grow the economy.”

According to Austin, state government can play a hand in reversing the trend. He writes in a piece for the Kansas Policy Institute that the fastest growing states are those with governments that spend and tax less. Wages and jobs grew 10 percent faster in low tax states compared to Kansas.

“The information suggests that the key to reversing Kansas’s 40-year long economic stagnation is efficient government fiscal policy,” Austin writes.

In 2016, Kansas citizens had a state and local tax burden of $4,495 per resident, the 26th highest in the nation, while nearby states like Oklahoma and Missouri offer very similar state services for far less. Census data showed an Oklahoman’s state and local tax burden of $3,456 in 2016, fourth best, while a Missouri taxpayer’s burden equaled $3,661, 10th.

LinkedIn’s analysis suggests that one challenge for mid-size cities like Wichita is that the workforce is leaving for larger cities like Dallas-Ft. Worth, Los Angeles, and Houston.

LinkedIn’s analysis suggests that one challenge for mid-size cities like Wichita is that the workforce is leaving for larger cities like Dallas-Ft. Worth, Los Angeles, and Houston.

The Associated Press reported on just such a trend last spring, noting that smaller cities are shedding population while larger communities are growing. Austin says when manufacturers focus on capital wages increase, but the number of jobs decrease. As large numbers of lower skilled workers depart, white collar service industry workers like lawyers and accountants typically aren’t far behind.

Watkins says Wichita’s challenge isn’t that people are departing for other states. It’s a workforce development issue that Wichita’s civic and business community is working on.

“If you’re going to have a problem, this is a good one to have,” Watkins says. “We have high paying jobs and we need people to fill them. That’s much better than the alternative–having high qualified people and no place for them to work.”

Watkins says one solution involves letting people know that today’s advanced manufacturing requires special skills and offers a good living.

“Today’s advanced manufacturing are not the factories your grandfather worked in. They are highly safe, clean environments,” Watkins said.

Local and state officials also are working with K-12 education and Regents institutions like Wichita State University to help develop curriculum that matches people and skills with jobs available. Wichita also has a serious student achievement problem. The 2018 state assessment shows only 7 percent of low income 10th graders are on track to be college and career ready in Math, and just 26 percent of the rest are on track.

Watkins is also hoping to have legislation introduced that is similar to an Iowa program. Iowa’s 260e, also known as the Iowa Industrial New Jobs Training program, offers employee training for new positions within the state. It’s financed through bonds issued by the 15 of the state’s community colleges.

“There’s no one magic bullet that solves this problem,” Watkins says. But he’s hoping it’s a start.