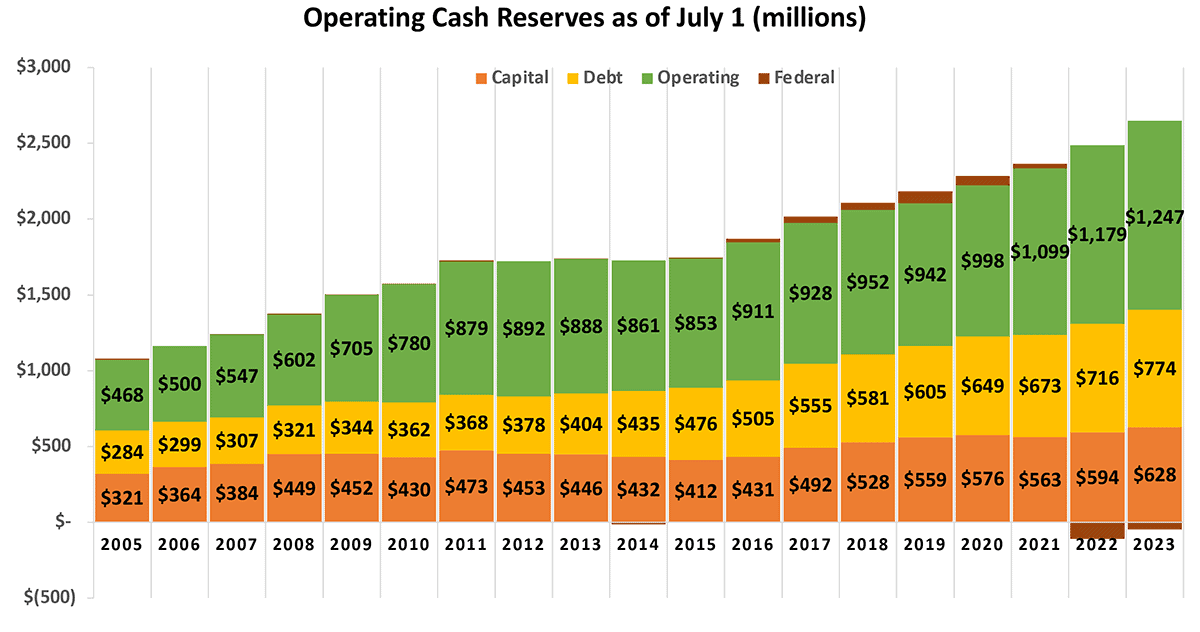

New data from the Kansas Department of Education show school districts collectively added $68 million to their operating cash reserves in the last school year, bringing the total to $1.25 billion.

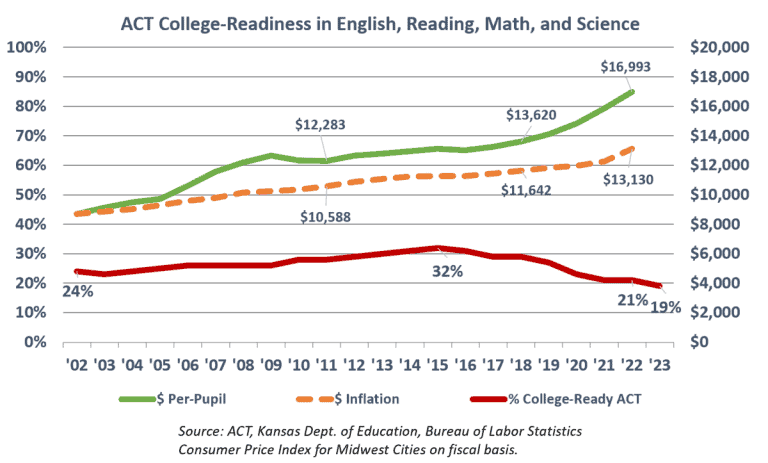

At the same time, Kansas ACT scores have fallen to a 30-year low, and a state audit found that increased spending simply does not correlate to improved achievements, school districts and the education bureaucracy are crying poor and demanding increased funding.

Operating cash reserves exclude balances in Capital Outlay, Federal, and Bond & Interest. Funds operate like checking accounts; the ending balance increases if more money goes in than is spent. Taken collectively, the increase in operating cash reserves indicates that school districts did not spend all of the state and local tax dollars provided last year.

Some of the largest increases in operating cash reserves include Blue Valley ($9.4 million), Wichita ($9.3 million), Shawnee Mission ($9.2 million), Lawrence ($8 million), Emporia ($3.7 million), and Salina and Olathe each added $3.5 million. Cash reserves held by each district are posted at KansasOpenGov.org.

Additionally, while there has been a drive to “fully fund” special education, special education cash reserves grew by an estimated $8 million.

State law calls for the Legislature to reimburse districts for 92% of their ‘excess costs’ after allowing for federal aid and state aid provided for the regular education of special education students. The reported reimbursement percentages have been below 92%, but the calculation does not count all of the money related to special education. Counting all funds provided, school districts receive more than 92% reimbursement.

Indeed, operating cash reserves increased by $779 million since 2005. Even while district officials were in court claiming to be underfunded, they didn’t spend all of the state and local tax dollars provided.

Districts want more money despite increases in operating cash reserves

At legislative hearings in September Scott Rothschild, the communications editor for the Kansas Association of School Boards claimed Kansas education funding — despite years of increases to satisfy Gannon lawsuit requirements — hasn’t kept up with inflation.

“Kansas funding was below inflation and takes a real dip from 2009 to 2015,” he said. “Total Kansas funding dropped from 98% of the U.S. average in 2009 to 88% in 2019. Over that period Kansas NEAP scores fell from above the U.S. average to about the same as the U.S. average. Kansas began increasing school funding more than inflation in 2018 under the 6-year funding plan in response to Gannon but as you can see we are still below the national average by about 10% and we are just about the regional average.”

However that simply isn’t the case.

Per-pupil spending in Kansas had been growing faster than the rate of inflation in 2006 and has stayed steadily above it ever since, despite the dip Rothschild describes, which coincided with cuts initiated by former Democratic Governor Mark Parkinson; Parkinson concluded Gov. Sebelius’s term that ended in January 2011. Adjusted for the cost of living (a dollar spent in Kansas buys a lot more than a dollar spent in New York), per-student spending in Kansas is the 9th-highest in the nation.

Moreover, achievement has been dropping precipitously. State assessment results were falling before the pandemic and are now lower still. College Readiness on the ACT declined from 32% in 2015 to now just 19%

Perhaps not coincidentally, outcomes started trending down around 2016 — roughly the time the “Kansas Can” standards were published by the Kansas State Department of Education, which prioritizes Social Emotional Learning over academic preparation.