Parents frustrated by COVID school closures may soon be able to enroll students in neighborhood microschools in Kansas, according to microschool operator Prenda.

Microschools solve many of the challenges teachers, students, and parents face in more traditional school settings or in homeschools, says Rachelle Gibson, enrollment director at Prenda. Students learn at their own pace and the microschools host fewer students than a typical class size, with only five to ten students attending each school.

“All of the pacing issues as a teacher are solved. They solve for homeschool parents the social piece,” Gibson said. “Women who would like an income but want to be involved with their kids, it solves that piece.”

Arizona resident Kelly Smith founded Prenda in 2018. It started with seven neighborhood kids gathering around his kitchen table for school every day.

“He was making it up as he went,” Gibson said.

By fall of 2018, three microschools hosted students in Smith’s hometown in Arizona. Today, Prenda boasts about 390 microschools in two states with 3,800 students. Prenda will expand to Louisiana and Kansas soon.

According to state Sen. Molly Baumgardner, the timing couldn’t be better.

Kansas parents are scrambling to educate their kids right now, Baumgardner said. A Louisburg Republican, Baumgardner chairs the Senate Education Committee.

“When I look statewide at what is and isn’t happening during the COVID pandemic, there is no equity in the education that is occurring in this state at this time,” Baumgardner said. “And there hasn’t been since the Governor had that press conference back in March saying we’re closing the schools.”

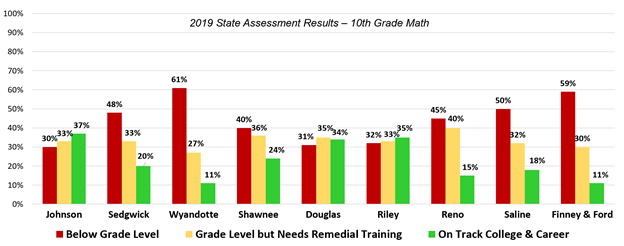

Student achievement was already low and declining before districts chose to restrict learning. Statewide, 41% of 10th-graders are below grade level in math on the state assessment test; 34% are at grade level but still need remedial training, and only 25% are on track for college and career. Even Johnson County schools, often promoted as being the best in the state, have 30% below grade level and only 37% on track for college and career.

Prenda is seeing explosive growth in the face of pandemic-related public school closures, according to Gibson. However, the organization’s goal isn’t to challenge public schools. It’s to provide options for families.

“We’re not coming in to say we’re the solution,” Gibson said. “We’re saying, here are the tools, and here is the funding to be the solution in your own neighborhood.”

Self-directed learning

Prenda microschool classrooms often meet in private homes. Some meet in churches or community centers. Each classroom includes between 5 and 10 students, ideally within three grade levels. A guide leads the small group and is free to offer one-on-one assistance when needed. However, students direct most of the learning.

“Learner autonomy is critical,” according to Gibson. “It’s self-directed learning inside of a framework.”

When a student first enrolls in a Prenda microschool, a guide helps assess the student and helps the student decide where they want to go. For instance, if a student is reading below grade level, the student might desire to read at grade level by the end of the year.

“Then we do the calculations and tell the student, that means you need to do this much,” Gibson explains.

Prenda doesn’t require its guides to be licensed teachers, though Prenda conducts background checks and formally vets its guides. Many are parents who have experience working with children.

Students set short-term and long-term goals for reading, writing, and math. They verbally share their goals and then Prenda’s software helps students remain accountable. Gibson says the process is interactive.

“Students know what they have to tackle each day, and the guide is free to offer one-on-one support or students are free to ask their classmates. But the guide is very rarely providing direct instruction to the entire group,” Gibson said.

Each day starts with a community circle where students share a struggle and success. That’s followed by a “Conquer” period in which students log on to various curriculum programs to meet reading, writing, and math objectives for the day. Later, the students shift to a collaboration period, where they debate, hold Socratic discussions, or work on group projects. Every day a different student leads the collaborative effort. Finally, students spend some time in “Create” mode, in which they work on projects like crafting a video or drafting a report.

“The principles are communication and social interaction,” Gibson said. “It gives them this space to learn how to interact with other people. And guides are charged and trained with conflict resolution.”

According to Prenda’s website, the schools focus on “creating flexible learning environments that combine strong academics, caring and inspiring social communities, and project-based learning experiences.”

“In our model, students take responsibility for their own learning, unlock their potential and see amazing results,” the site reads.

Who Pays?

Parents can pay a monthly fee of about $100 per student to enroll in Prenda microschools. Or, some families choose to collaborate and pool their own resources to start a Prenda microschool. In some states, Prenda contracts with a public school to provide services.

In Kansas, Prenda hopes to partner with a public school, which would allow taxpayers to foot some or all of the bill for kids enrolled. Kansas taxpayers provide a flat fee of $5,000 per student for kids enrolled in virtual public schools; average funding for all students will be more than $16,000 per student this year.

Per-student funding is even higher in the smallest districts in Kansas. For example, USD 511 Attica in Harper County had collected $18,758 per pupil in total funding; Superintendent Michael Sanders was paid more than $133,000 to manage the tiny district, with just 155 students and 37 employees.

Enrollment in public schools down 22,000

Preliminary enrollment reports show enrollment is down more than 22,000 students this year, as parents are pulling students from districts that aren’t offering full-time in-person learning.

In many cases, districts have no immediate plans to return students to classrooms after the holiday break. Baumgardner’s senate district includes eight public schools in Johnson and Miami counties. At one district that Baumgardner represents, Gardner-Edgerton USD 231, middle and high school students started virtual school last March. To date, they have yet to enter a school building. The district has no immediate plans to return students to classrooms when the new semester starts.

“Parents are tremendously frustrated,” Baumgardner said. “There are those who can’t afford to send their kids to a private school or don’t have the transportation to get them to and from a private school. And they don’t have the means to work and to be a teacher and para, which is what’s required while the kids are in virtual learning.”

Baumgardner suspects that virtual learning experiment isn’t working well for many families. However, state data is limited for now.

“It’s important to us to know what the communities, faculty, teachers, children, parents are going through, but we don’t have a clear snapshot of what has happened statewide,” Baumgardner said.

Recent studies hint at troubles

A report from consulting firm McKinsey and Company estimates that students could lose 5-9 months of learning by the end of the school year. Like middle and high school kids in the Gardner Edgerton School District, students in the nation’s largest school district in Fairfax County, Virginia, have been learning online since March. The number of middle and high school students earning F grades increased by 83 percent in that time, according to a Washington Post report.

Researchers from Stanford examined test scores in 17 states and the District of Columbia to determine that the average student lost one-third to a full year of education since the lockdowns in March. Meanwhile, virtual students are struggling with mental health issues. The Blue Valley district lost at least two students and a principal to suicide since the lockdowns began.

Microschools provide some socialization and opportunities for assisted and autonomous learning.

Unions oppose microschools

The nation’s largest teachers union isn’t impressed. As reported in the Wall Street Journal, the National Education Association issued an opposition report that addresses Prenda.

The NEA report notes that microschools address some limitations of homeschooling and some of the equity issues related to education savings accounts. But it also lists several complaints.

“Prenda provides no physical space, no transportation, no Internet connectivity, and no meals,” the report reads.

The NEA raises concerns that Prenda requires parents and students to sign computer policies to use Prenda devices, but “the company is silent regarding its commitment to secure student and parent data…” the NEA document reads.

The growth of microschools drew the interest of a Wall Street Journal opinion writer and the ire of the NEA.