Remember the promises about fiscal responsibility and upholding the rule of law from people running for state office over the years? Some of those promise-makers apparently didn’t mean it.

State statute, K.S.A. 75-3721, says the governor’s budget cannot include expenditures that require additional uses of revenue, meaning the budget should only spend existing resources. Statute also requires that the budget proposal maintains an ending balance equal to 7.5 percent of expenditures.

According to former Speaker of the House Mike O’Neal, the budget Gov. Laura Kelly submitted in January didn’t comply with state law. O’Neal says the last four administrations have done the same.

Lawmakers and the Governor can ask the Kansas Legislative Research Department (KLRD) to draw up a draft budget profile using certain assumptions, but often the profiles eliminate statutory requirements. The Governor provides the initial budget outline lawmakers use to craft the budget, and the assumptions the Governor builds into her proposal are built into future profiles. That can make the budget appear to be healthier than it actually is.

Kelly’s proposal included an ending balances of 9.5 percent of expenditures in 2019 and 9.1 percent in 2020. However, the proposal included a number of gimmicks to pad the state’s bottom line, including provisions that required lawmakers pass legislation to draw new revenue, and that doesn’t comply with state law according to O’Neal.

When lawmakers request budget profiles to show how one tweak might affect the entire budget, legislative research typically builds in the assumptions from the Governor’s initial budget proposal. This allows them to ask researchers for a prospective budget in which reserves dip below the required 7.5 percent without accounting for it. Over the years, final budgets approved by the Legislature have not had the required ending balance.

“The legislature puts a proviso in the budget that then says we’re not going to meet the 7.5 percent,” Rep. Dan Hawkins, a Wichita Republican, says. “That’s how they get by without doing it.”

Basically, they change the ending balance law to say ‘except this year’ and media doesn’t say a word.

“Research uses certain assumptions to create any profile that an individual lawmaker wants,” says O’Neal. “But those assumptions have to be based on reality.”

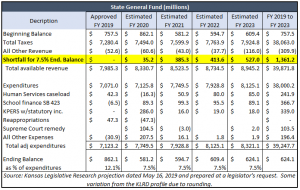

The table below comes from a KLRD budget projection prepared for a legislator last week; it contains spending approved in this year’s budget and extends through FY 2023 with only a few increases estimated by KLRD for higher student enrollment and human services cases. Revenue estimates include Gov. Kelly’s veto of the tax reform legislation, assume highway transfers will occur as Gov. Kelly recommends and that other transfers will be the same as in recent years.

It also adds a revenue line to show the additional amounts needed each year to maintain the statutory ending balance without cutting approved spending. Next year’s budget is about $35 million short; the shortfall balloons to $385 million for FY 2021 and the next two years jump to $414 million and $527 million, respectively, for a four-year shortfall of $1.36 billion.

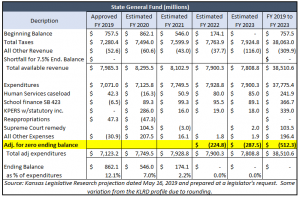

The traditional budget projection used by governors and legislators, however, shows a much different picture by allowing the ending balance to hit zero before making adjustments. The following table shows no adjustment needed until FY 2022, reducing expenditures by $225 million to hit a zero ending balance. FY 2023 spending would also have to be reduced by $288 million to hit zero.

Budget projections typically don’t extend beyond the current cycle (FY 2019 and FY 2020), so legislators and reporters would see, in this case, a 7 percent ending balance in FY 2020 and that’s where the report ends. Many know of the iceberg lurking beneath the surface, but that’s not shared with citizens.

According to J.G. Scott, acting director of Kansas Legislative Research Department, budget profiles are simply a snapshot.

“It’s not a prediction on what we think will happen,” Scott says. “It’s a planning document that looks at trends.”

He says the further out in time a profile stretches, the less accurate the numbers.

“I guarantee, it’s going to change,” Scott says.

According to Hawkins, House rules create an incentive for lawmakers to spend money. Several years ago, the House adopted a rule that essentially says lawmakers can only add spending to the budget bill if it’s budget neutral. Known as pay-go, it basically forces legislators to say what they’d cut in order to increase spending elsewhere. But lawmakers made a change to that House rule in 2017. If a budget makes it to the House floor with an ending balance above the 7.5 percent ending balance, the pay-go rule doesn’t apply.

“That means legislators can add as much spending as they want during the debate as long as they can get the votes to add it in,” Hawkins said.

For that reason, he says it’s not in the interest of fiscal conservatives for a budget to reach the House floor that actually meets the 7.5 percent ending balance requirement.

“All it did was create a perverse incentive for us to spend, spend, spend,” says Rep. J.R. Claeys, a Salina Republican.

Conversely, if the Governor wanted to give lawmakers in her party the opportunity to slip spending into the budget without having to say what they’d cut to fund it, she could propose a budget that built in a larger than 7.5 percent ending balance. That’s what she did, but it required specific legislative action for it to reach the floor with that balance in tact. That didn’t happen. The budget increased spending by nearly 9 percent over last year, and most budget profiles show a large enough ending balance for one year. Things go south as profiles assume legal budgets that don’t sweep highway funds or use other proviso gimmicks in years further out.

Claeys says there’s only one way to guarantee reduced government spending.

“The thing that stops spending is having legislators that will stop spending,” Claeys says.

Citizens may wonder whether that will happen before or after snowballs freeze in Hades.