The International Foster Care Organization defines foster care as “… a way of providing a family life for children who cannot live with their own parents.” Neglect and abuse are the most egregious reasons children are separated from their parents but politics, oddly, drives most foster care discussions.

For example, it was front-page news in 2017 when children were discovered to be sleeping in offices of Kansas Department of Children and Families while waiting to be placed with foster families. Media railed against the Brownback administration for allowing that to happen, but when the same occurred recently under Democrat Laura Kelly’s administration, it was largely downplayed.

Just last week, Governor Kelly’s administration announced a series of controversial – and arguably unconstitutional – new requirements for foster parents of LGBTQ youth. The Wichita Eagle says one such recommendation would allow a boy who identifies as a girl to be allowed to share a bedroom with foster parents’ biological female daughter.

The first step in improving foster care issues in Kansas may be reaching tri-partisan agreement (Democrats, Republicans, and media) to set politics aside.

Kansas #41 in the nation

Kansas has more kids in foster care per 1,000 residents than 40 other states, according to data compiled by the Annie E. Casey’s National Kids Count Survey. There were 10 kids in foster care in Kansas for every 1,000 residents in the state between 2010 and 2016, the latest year for which data is available. Only West Virginia (16), Montana (15), Alaska (15), Indiana (12), and Vermont (11) had higher numbers of children per capita in foster care than the Sunflower State. Oklahoma and Arizona tied with Kansas.

At the lower end of the spectrum, only three kids per every 1,000 residents in Virginia, Utah, New Jersey, Maryland, and Idaho are in foster care.

Kansas Sen. Richard Hilderbrand called the numbers “alarming.”

“We need to figure out why,” he said.

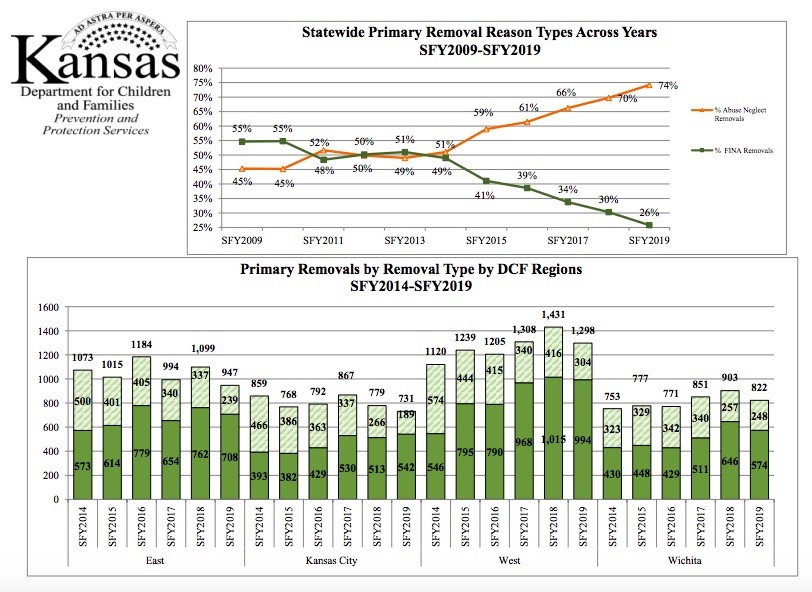

The Kansas Department of Children and Families removed 3,798 kids from homes last year, including 26 percent who were removed for non-neglect, non-abuse reasons. Some states won’t remove children from their homes for non-neglect, non-abuse reasons. States define non-neglect and non-abuse cases differently, but many states don’t remove children unless there is a real fear for the child’s safety.

Kansas DCF deems non-abuse, non-neglect removals as “Family in Need of Assessment (FINA) removals. They included removals for things like a child’s disability, truancy from school, or a parent’s alcohol addiction. As an example, 58 Kansas kids last year were FINA removals taken from their families due to inadequate housing, another 183 children were FINA removals due to a child’s behavioral problems.

Martin Guggenheim, a law professor at New York University, says neglect is typically associated with poverty.

“Cases that lead to children coming into care or coming to the state’s attention, even as potential cases for removal, commonly involve a poor, single parent with limited resources who sometimes is living in inadequate conditions because that’s what’s available,” he told PBS Frontline.

Kansas is removing fewer children for FINA reasons than they did a decade ago. Back in 2009, more than half of Kansas kids removed from their homes were taken for family assessment reasons. In 2019, only about a quarter of the kids removed from their families were taken for non-abuse, non-neglect reasons. Still, the number of kids in foster care per capita is stubbornly high, and the volume of the alarm bells seems somewhat dependent on who is occupying the Governor’s office.

Media Scrutiny into Kansas Foster System Wanes

Hilderbrand isn’t only worried that Kansas has a higher percentage of kids in foster care than other states. He wants to evaluate the entire system.

“I think it’s broken,” he said. “We have to evaluate from when the child comes into the system. Is there something going on that’s causing more kids to enter into the system? Or is it once they’re inside the foster system is that the issue?”

Officials rang alarm bells in 2017 after three girls went missing from foster care in Tonganoxie. They ran away but were returned to care a few days after the story broke. In the meantime, lawmakers on a child welfare task force learned that more than 70 kids were missing from Kansas foster homes. It created a firestorm, but media has since been largely silent on the topic.

Then-Sen. Laura Kelly, a Topeka Democrat, told the committee she was “flabbergasted.” She blasted then-Kansas Department of Children and Families Secretary Phyllis Gilmore, appointed by former Gov. Sam Brownback.

“She’s responsible for these kids,” she told public radio’s news service. “They are wards of the state, and she’s in charge of the agency.”

Rep. Jim Ward, a Wichita Democrat, called for Gilmore to be fired.

“If this was a single event, I would be more willing to listen,” he told KCUR. “But this is on top of last (month’s) revelation that some foster care kids were sleeping in offices…This is absolutely unconscionable.”

Foster Kids Sleeping in Offices Again

Gilmore stepped down less than two months later, shortly before Brownback resigned the governorship for an ambassadorship in the Trump administration. His replacement, Gov. Jeff Colyer, appointed Gina Meier-Hummel to lead the Kansas Department of Children and Families.

She threatened to levy fines for children sleeping in offices to the state’s private contractors responsible for operating Kansas foster care. From October 2018 – December 2018, no foster kids overnighted in offices. Kelly’s administration dropped the threat of fining contractors in January, and the number of kids sleeping in offices inched higher. In April of this year, 27 children spent the night in offices, and 90 kids were missing from Kansas foster care.

There was little public outrage, though the Associated Press made note of the spike in the number of children sleeping in offices in May.

“The return of having to have foster children stay overnight in offices received little public attention since Kelly became governor,” the AP reported.

The numbers dipped by summer. On July 18, DCF reported 59 children were missing from its care. The problem, however, hasn’t escaped the notice of Wade Moore, a Pastor and the founder and dean of Urban Preparatory Academy in Wichita. McAdams Academy leases Urban Prep Academy facilities to service youth in foster care.

“You see these kids show up at the beginning of the day with backpacks full of all their belongings, and at the end of the day, they pack up all of their belongings and go back to the offices or wherever they sleep at night. Every day we see this,” Moore said.

They’re often teenagers or kids with behavior problems, and not having a place to sleep can exacerbate their challenges.

“Those kids that show up every day at our facility, they’re frustrated,” Moore said. “They haven’t had any sleep. They may not have had anything good to eat. They break out windows. They harm themselves, and some of them run when they get an opportunity.”

Most states have a shortage of foster homes available, according to Naomi Schaefer Riley, a resident fellow on child welfare and foster care at the American Enterprise Institute. States used to be able to rely on congregate care or orphanages. Group homes often housed kids with behavioral problems, large sibling groups, or older children who didn’t have any interest in finding a new family.

“Unfortunately, we are in the process as a country of closing down group homes,” she said.

President Trump signed the Family First Prevention Services Act into law in February 2018. The new law prioritizes keeping families together and eliminated some federal reimbursements for congregate-care facilities.

“Those are the last resort, and not having them is creating problems for a lot of states, meaning kids will be moving around a lot more,” she said.

“You want to do what’s best for the kids, because it goes from taking too many kids out and that’s a news story, and then you stop taking kids out and have more incidents of abuse,” a former DCF administrative employee said. He did not want to be named in this story. “It’s also really traumatic for kids to be taken out of their homes.”

Technology Upgrades Could Help

Several things can trigger a DCF investigation and the temporary removal of a child. If a kid misses too many days of school or a teacher sees odd bruises, that can result in a visit from a social worker.

Determining whether a child is removed from a home is often a subjective decision, according to Riley. She says predictive risk modeling and algorithms can assist professionals in determining whether a child is at risk for abuse or death in a home.

“Predictive risk modeling is a great development because right now, it’s a very subjective standard,” she said.

Former DCF officials hoped to purchase or build a structured decision making (SDM) tool to assist social workers with risk assessment. Such an app would allow social workers to access information from police, healthcare providers and other sources and to input factors that the software could generate the likelihood of further risk to the child.

Currently, when a teacher or health care provider calls the DCF hotline to report a child may be in danger, call center staff attempts to check additional information like arrest records and whether they’ve received other calls on the same subject before sending a social worker into the field. The technology is archaic, according to one former DCF official. Updating the system would likely cost millions, though there are federal match programs available.

Riley believes child protective services workers would benefit from training similar to what first responders and law enforcement receive.

“Let’s say you’ve got a report of domestic violence. You’d send a police officer over there, and they’d talk to both parties,” Riley said. “They have a very specific way to determine what happened. The CPS workers in many states are not trained in those investigative techniques. They are making just very subjective judgments.”

However, she said wondering why Kansas has so many kids per capita in foster care isn’t the question policymakers and the administration should be asking as they attempt to improve the state’s child protective services.

“The fact that you have a high number of kids in foster care is not in and of itself a problem. The issue I am most concerned about is whether children are being abused or neglected,” Riley said. “A lot of states have lowered the number of kids left in dangerous situations, and that’s sort of the headline.”

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story was misleading because it didn’t clarify the relationship between McAdams Academy and Urban Prep Academy. McAdams leases Urban Prep facilities, which it uses to assist kids in foster care.