At a recent Wichita City Council meeting members grappled with what to with the WaterWalk development. The old Gander Mountain building was sitting empty and a company wanted to move in, but the ground lease would not provide rental income to the city. Wichita still owes $1.7 million on WaterWalk. Moreover, with the west bank development including a $75 million baseball stadium going in, council members wondered out loud if this was the best use of prime riverfront real estate.

For all outward appearances it was a typical city council meeting, but the problems underpinning the debate all tie back to incentive-driven developments approved by the city. Over the past 15 years city officials have become enamored with subsidies. For example a city webpage for Community Improvement Districts (CIDs) lists the millions in subsidies handed out by the city.

Former Wichita Mayor Carlos Mayans was never pleased with the WaterWalk deal.

“The WaterWalk Project was rushed to a vote before I took office in order to have my hands tied as much as possible,” says Mayans. “The one-page contract allowed Mr. DeBoer to lease the land for $1 a year for 99 years and the only person that was authorized to enhance and/or change the contract was then City Manager Chris Cherches without approval from the City Council.”

The WaterWalk deal was put in place long before any current city council members were in office, but as the development of the baseball stadium proves, incentives have become more ingrained in city government, not less.

Dr. Russell Fox, a political science professor at Friends University, says the rise of incentives and subsidies to pay for development is not new.

“On the one hand this is terrible way to run a city, it is a way of spending money and a way of pursuing projects that systematically leaves people feeling excluded.” Fox continued, “It leaves small businesses feeling pushed aside. It undermines the ability of a city politician to build a sense of trust. And it really undermines the ability of citizens to feel a sense of ownership of what is going on.”

The Competition Churn

The use subsidies to get businesses to move, as seen with the baseball stadium or creating activities for economic churn like the Stryker soccer complex, is now common place. Even the building that was once occupied by Mead’s Corner received a subsidy to develop an office building to house IMA insurance. The city is using incentive programs to back private business ventures that compete for leases with existing companies.

The Sentinel has spoken with a few commercial real estate businesses about how developments backed by city incentives are able to undercut the price on existing office space by as much as 20% due to the subsidies provided by the city and, ultimately, taxpayers. It is worth noting that no business was willing to be quoted about being put at competitive disadvantages for fear of reprisal from the city.

Wichita officials have injected themselves into the development process in such a way that actual business leaders are afraid to speak openly about it for fear it will hurt their chance to grow and develop. For evidence of the city’s dominance in commercial real estate, look no further than the WaterWalk agreement. King of Freight is moving into the Gander Mountain facility from their current location in the High Touch Technology building, which is in fact owned by the City of Wichita.

“Yes, this is a bad way to run a city,” says Fox. “The other side of it though is that this is the way almost all cities run.”

Mayans remembers how the incentives were used when he took office.

“I did have deep concerns about what we were calling incentives because they were not.” Mayans continued, “I understand that sometimes government can play a helpful role in enhancing the opportunity of investment by the private sector, but what they were doing in Wichita was loaning money to developers with no interest or repayment period, disposing of land and property worth $10 million for a mere $200,000.”

Giving land away at a deep discount happened as recently as March, when the City Council voted to sell 4 acres of land next to the stadium development to the developers for $4 dollars. There has not been public disclosure of everyone who is involved with the development group.

It is actions like this that Fox says speaks to a need for city politicians to look like they are doing things.

“I am not aware of any kind of critical mass of people saying, ‘oh my gosh the wingnuts and Lawrence Dumont are failing us,’” says Fox. “So, what you really had was a mayor, for all I know he is a real committed baseball [fan], but more importantly he said this is a big thing I can do. City politicians want to be able to show things.”

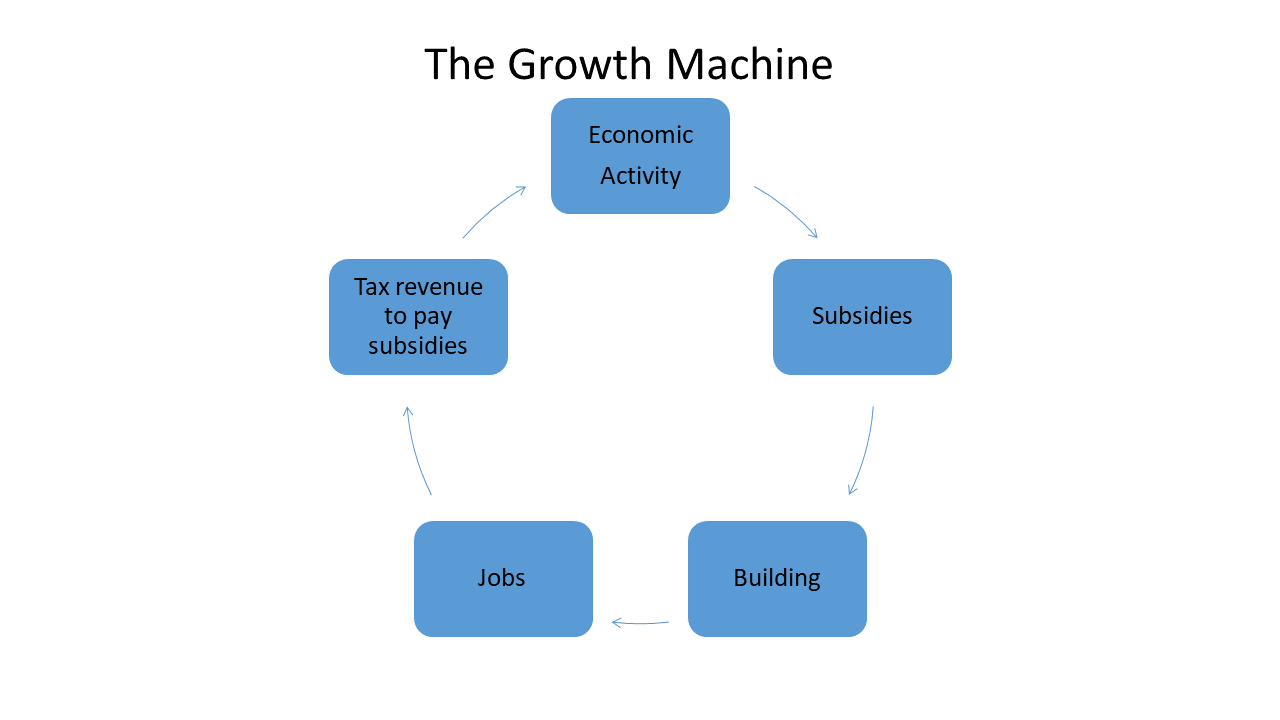

The Growth Machine

Fox describes the structure to create economic activity as a growth machine with cyclical activity. Politicians look to create economic activity, so the city finds a business to move or expand but it wants a new building or some other incentive. The city approves a subsidy, which theoretically creates jobs and produces economic activity, and the incremental tax revenue is used to pay down the subsidies. But the cost of government continues to rise, and since incremental tax revenue from these deals aren’t available to cover operating costs, everyone else absorbs a bigger tax burden. Meanwhile, the city isn’t growing much so politicians pursue more incentive deals.

“This is why a city like Wichita, a city like other cities around the country, that are not growing, not really, not in any significant way,” says Fox

Economic incentives are increasingly coming under a critical eye. A study by North Carolina State University found that while incentives do create economic activity, they have a net negative impact on the economy overall.

“While incentives may draw in more economic growth, they also pull resources from the government’s coffers and may commit future funding for public services that benefit the incentivized business. Using a panel of 32 states from 1990 to 2015, we seek to understand how incentives affect a state’s fiscal health. After controlling for the governmental, political, economic, and demographic characteristics of a state, we find that incentives draw resources away from the state. Ultimately, the results show that financial incentives negatively affect the overall fiscal health of a state.”

Fox is not surprised.

“City politicians even if they don’t want to, even if their interests are ideological, they are almost forced to create stuff to show voters,” says Fox. Yet he is keen to note Wichita is not alone in this.

“None of that is fundamentally all that different from what, Tulsa, Des Moines, or Omaha or any number of other cities, that is in fact the normal way most cities operate,” says Fox.

Mayans feels that ultimately, city government should not pick the winners.

“We have to be careful with any incentive because as elected officials we have a fiduciary responsibility when allocating the tax payers money,” says Mayans. “We should make every effort to help in other ways (permits, regulations, etc.) instead of money. We should not pick the winners or the losers.”