Kansas education commissioner Randy Watson earlier this week told the State Board of Education that “proficient is a made-up term that the federal government makes us define.” Watson and others at the Department of Education know better, but this is just the latest example of state officials deceiving people about low student achievement in Kansas.

The report comes from Topeka Capital-Journal reporter Rafael Garcia, who tweeted Watson’s quote at the February 14 school board meeting. As of this writing, the video recording of the board meeting has not been posted.

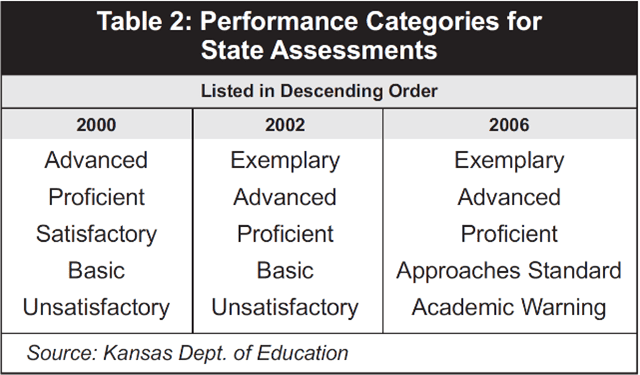

‘Proficient’ is not a made-up term. In fact, the Kansas Department of Education (KSDE) has had performance categories named ‘proficient’ on past iterations of the state assessment, as shown on Table 2 from Removing Barriers to Better Public Education. KSDE later purged  easily-understood terms like ‘proficient’ and ‘advanced’ with labels like ‘Meets Standard’ and ‘Level 1.’

easily-understood terms like ‘proficient’ and ‘advanced’ with labels like ‘Meets Standard’ and ‘Level 1.’

Garcia says Watson made that statement in response to claims that Kansas students aren’t “proficient.” He said Watson told board members that they can easily move to lower its proficiency standards like other states have done. But that would not be the right thing to do, he said. (This is classic KSDE double-talk; ‘proficient’ is made up, but we have high proficiency standards.)

Several board members were upset that the state’s “high standards are used to attack K-12 public schools’ success outside of the board room, particularly in the Kansas Statehouse.”

Translation: board members are upset that legislators and parents are learning about persistently low achievement levels. And instead of taking action, some board members want to dismiss the problem with deceptive comments.

Both are true: standards are high, and achievement is low

The ‘high standards’ charade has been debunked many times, most recently in Giving Kids a Fighting Chance with School Choice. The following excerpt references a presentation by State School Board President Jim Porter to House K-12 Budget Committee last year.

Porter referenced a slide in the presentation from a National Assessment of Educational Progress report that shows Kansas has higher state proficiency standards than most states. According to the NAEP mapping study, proficient performance on the Kansas state assessment is higher than what NAEP considers proficient in three of the four cases (i.e., fourth-grade reading and math; eighth-grade reading and math).

Here is the implication of the NAEP mapping study in a practical example. In 2019, the state assessment showed that 29% of eighth-grade students were proficient in English language arts, and the 2019 NAEP results showed that 32% of Kansas eighth-grade students were proficient in reading. So since Kansas has a higher bar for proficiency in this measurement, it’s fair to say that the state assessment result of 29% is likely at or a little above 32% from a national perspective. But that is not at all what Porter told the committee: “We have set our assessment scores [proficiency levels] significantly higher than many other states because we want that to be a challenge goal. So when you hear that X% of students are performing at proficient or above and we should compare that to, well, typically Florida, you need to see where those rates are.”

Porter’s response had nothing to do with the question asked by Rep. Williams, and his Florida reference implies that he is either consciously deceptive or horribly misinformed.

States’ performance on NAEP is unaffected by state assessment standards. Students in every state take the same NAEP test, and it is fair to compare the results at face value. In fourth-grade reading for low-income students, 28% of Florida students were proficient in 2019, but only 20% of Kansas students were proficient. Porter’s reference to Florida is an attempt to dismiss its superior performance as a methodological anomaly.

By the way, it’s essential to differentiate between state “standards” and classroom activity. A standard determines what is expected of students to achieve a certain level of performance. For example, the tenth-grade reading standard in Kansas expects students to “cite strong and thorough textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.” The department of education determines the appropriate “cut scores” on the state assessment test that coincide with specific definitions of accomplishment such as “proficient”; it is akin to a teacher setting the cut score for an “A” on a test at 90% or higher. In terms of the NAEP mapping study, it would be like NAEP saying 90–100 is proficient, but Kansas uses a scale of 94–100.

Here are some examples of low outcomes that education officials are trying to suppress:

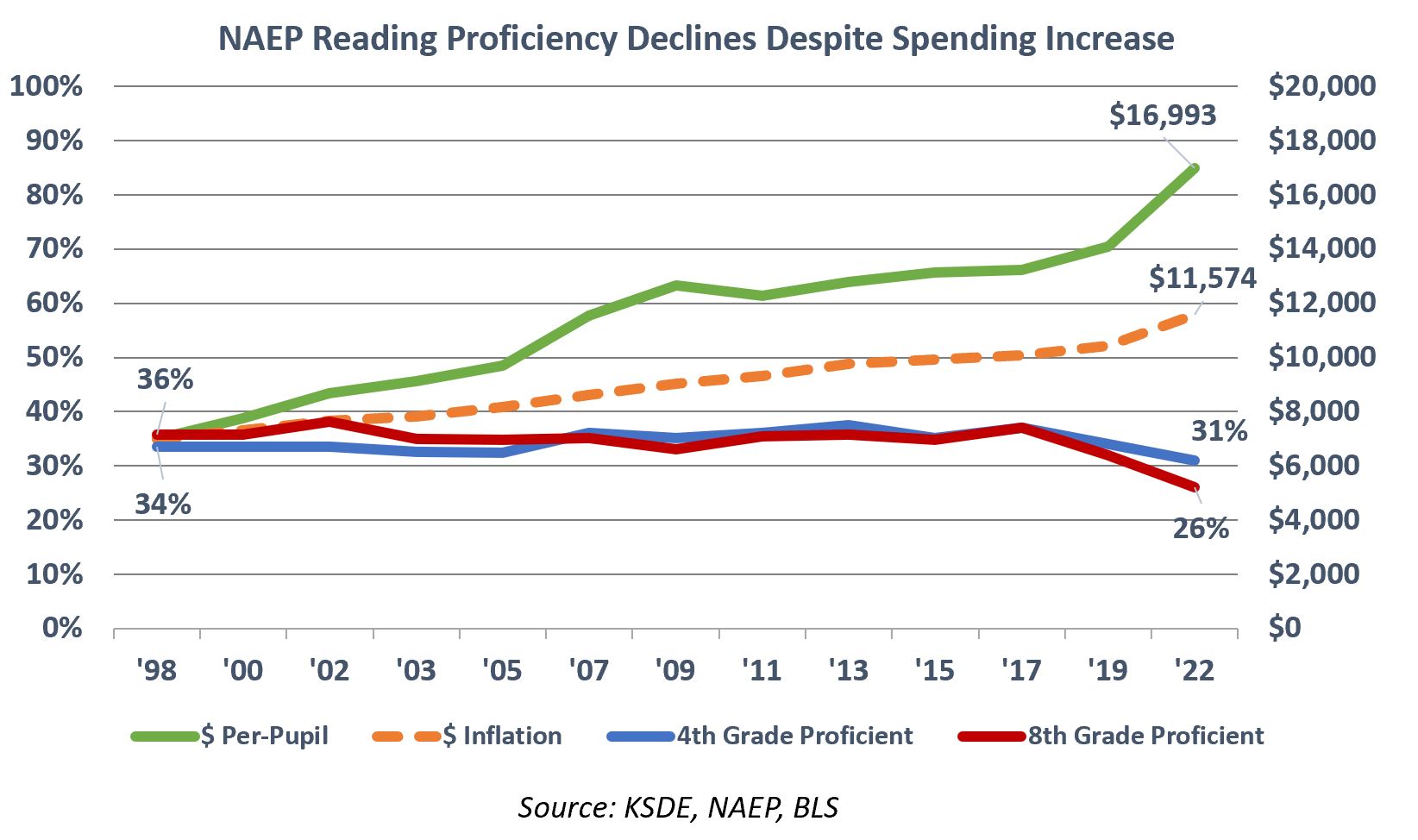

- Less than a third of Kansas students read proficiently, according to the 2022 NAEP.

- Only 21% of Kansas graduates who took the 2022 ACT were college-ready in English, Reading, Math, and Science.

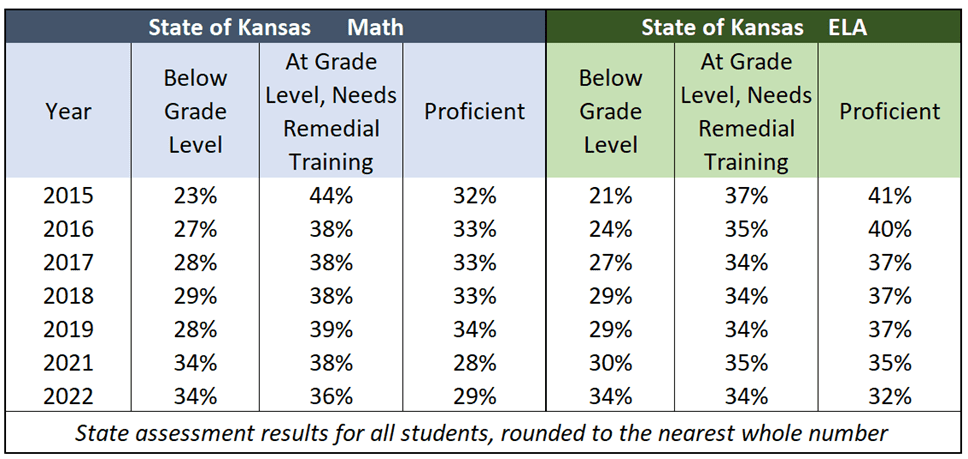

- The 2022 state assessment shows Kansas has more students below grade level than are proficient.

The Kansas Department of Education and the State Board cleansed the descriptions of state assessments of embarrassing terms like ‘below grade level’ and to give the appearance that every student is on track for college and career (with limited, basic, effective, or excellent understanding of material).

But no amount of spin can obscure the fact the state’s own tests show that achievement was declining before the pandemic, and achievement has never been as high as parents have been led to believe. As the saying goes, don’t try to tell me it’s raining outside while your dog is whizzing on my boots.

Sadly, Watson’s attempt to excuse away low achievement is just the latest in a very long line of education officials – either deliberately or accidentally – deceiving parents and legislators, de-emphasizing academic preparation, and even ignoring state laws designed to close achievement gaps and improve outcomes for all students. We tell many of those stories in Giving Kids a Fighting Chance with School Choice. Write to me at Dave.Trabert@KansasPolicy.org to get a free copy; then, you will understand why we believe that parents cannot count on public school system administrators to address the achievement crisis.