Lori L. Taylor, a Texas A&M professor, is set to deliver an educational cost function analysis to state lawmakers on March 15, but she gave legislators a preview of what they can expect during a joint education committee meeting today.

“We’re not going to be starting from the state’s funding formula weights,” she said. “We are starting from the observed outcomes of Kansas school districts.”

The Kansas Supreme Court ruled the current school financing formula unconstitutional. Justices gave lawmakers an April 30 deadline to complete a new one for Court consideration. Legislative leaders agreed to shell out $245,000 to Taylor and WestEd, a nonprofit, nonpartisan research consultant, for a cost-analysis of K-12 education in the state.

Taylor outlined the approach they would take to estimate what it costs to educate Kansas students to meet the Rose standards. However, she began her presentation by defending her work on a 2004 Texas case. The judge, she said, turned out not to be her greatest fan. He disagreed with her methodology.

Taylor outlined the approach they would take to estimate what it costs to educate Kansas students to meet the Rose standards. However, she began her presentation by defending her work on a 2004 Texas case. The judge, she said, turned out not to be her greatest fan. He disagreed with her methodology.

The judge wrote Taylor’s study “overemphasizes small district behavior and understates the urban influence on cost relationships,” but Taylor says she sleeps “just fine at night knowing what the Court has said about my work.”

“I am very motivated to get the understanding of what’s going on in the relationship in Kansas between student outcomes, school resources, what schools need and economies of scale and all the other factors that feed into a proper understanding of the cost of education for the state of Kansas,” she told the committee.

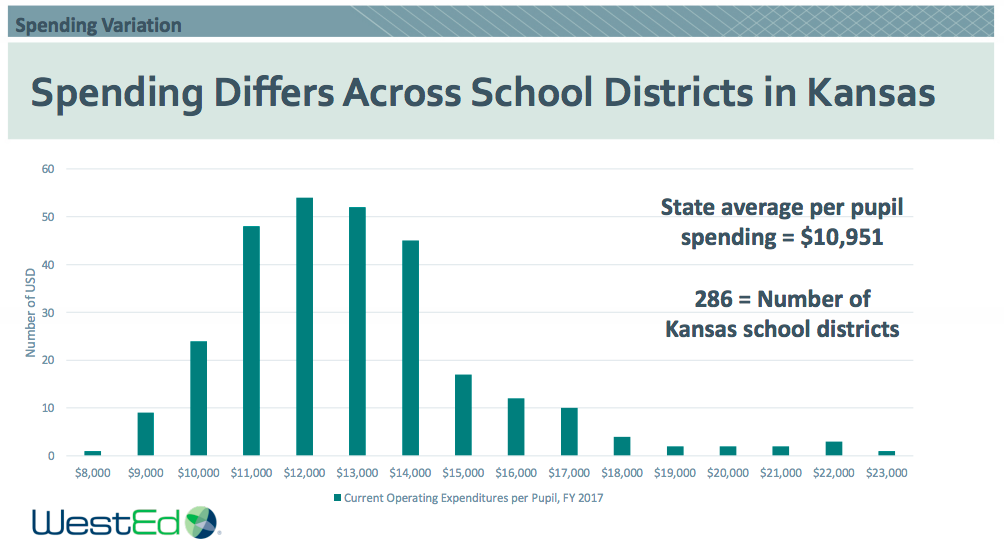

Kansas’ 286 school districts spent an average of $10,951 per pupil last year, though expenditures per pupil vary dramatically across the state. One slide showed some districts spent as little as $8,000 per pupil last year, while others spent up to $23,000 per pupil.

Jason Willis, a West Ed consultant, told the joint committee of state representatives and senators that research has reached a near consensus that it costs more to educate some students like those who are economically disadvantaged, disabled, or those learning English as a second language.

“The caveat here is that there is no consensus on how much more is necessary for these populations to achieve desired outcomes,” he said.

Taylor said their research will be limited to funding areas directly related to educational outcomes. So transportation funding and food services, for example, will not be included in the study.

“They’re not producing reading and writing and arithmetic,” she said. “They are different products.”

She also said the study will not recommend school consolidation, though it will examine how economies of scale affect costs.

“We found in the Texas context that most of the benefits of consolidation occur at the school level and not at the district level,” she said. “In the rural areas, it just doesn’t make sense. The kids are too dispersed.”

Taylor and Willis stopped short of making any formal recommendations during Friday’s meeting, though Taylor said their research will include identifying the best practitioners in the state so others can emulate them.

“To the best of my knowledge at this time, we have the data that we need. I think we are in a good position to be able to move forward with what you’ve tasked us to do,” she said.

The research should be concluded by March 15, and lawmakers will have a few weeks to hammer out a new finance formula to comply with the Court’s April 30 deadline.