Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin recently blasted Fairfax County school officials for their maniacal focus on equity after they withheld national merit award information from students until scholarship deadline applications passed. That’s just one example of a fanatical focus on equity that extends far beyond Virginia and suppresses (what should be) a zealous pursuit of academic improvement.

Take the National School Board Association, the group that encouraged the Biden administration to label parents as domestic terrorists. NSBA is hosting an Equity Symposium in Washington on January 28, and you can bet that your tax dollars will pay for a nice junket for school board members across the nation.

With student achievement in the proverbial toilet, attendees will learn how electric school buses advance equity and how Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) dollars can promote equity. Another session focuses on using public education as the foundation for a “just, multiracial democracy,” where attendees will learn how to handle “relentless attacks from the far right.”

You’d think that historically low scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, which wiped out two decades of learning, would prompt a school board association to help members deal with that crisis and the enormous achievement gaps for minorities and low-income students.

They could talk about reallocating resources to close reading gaps for Black students in public schools, who are more than two years’ worth of learning behind White students in the fourth grade. A session on Florida using choice, transparency, and accountability to take the Sunshine State from one of the worst states in the nation to one of the best could help school board members deal with income-based educational discrimination.

Only 9% of Black eighth-graders in this country and just 14% of Hispanic students are proficient in math, compared to 34% of White students. Florida still has achievement gaps, but that’s largely because both income-based cohorts have strong gains. Between 2003 and 2022, fourth-grade math proficiency for Florida’s low-income kids jumped from 16% to 29%, while the national average only moved from 15% to 20%.

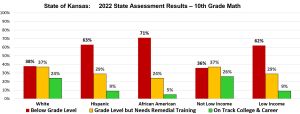

Race-based and income-based educational discrimination is also perpetuated by school officials here in Kansas. The majority of Hispanic, Black, and low-income high school students are below grade level. White students are about five times more likely to be proficient than Black students, and those who are not low-income are three times more likely to be proficient than kids from low-income families.

But too many public school officials show disdain for academic preparation, even in the face of an achievement crisis.

Per-student spending in Kansas was almost $17,000 last year, but school officials barely allocated half of their spending to instruction (costs associated with the direct interactions between students and teachers). The Kansas Department of Education says instruction is “the most important part of the education program, the very foundation on which everything else is built. If this function fails to perform at the needed level, the whole educational program is doomed to failure regardless of how well the other functions perform.”

Yet despite having more students below grade level than proficient and a $539 million funding increase, school officials allocated the lowest portion of total spending to instruction in recorded history. Just 52.8% of almost $7.9 billion was spent on direct interactions between students and teachers last year.

The Kansas Department of Education is celebrating record graduation rates, despite knowing that many who received diplomas cannot read and do math at grade level. As the late great Walter Williams said, “It’s grossly dishonest for the education establishment and politicians to boast about unprecedented graduation rates when the high school diplomas, for the most part, do not represent academic achievement. At best, they certify attendance.”

Equity in today’s education parlance means stifling the performance of higher achievers and telling low-income kids and minorities that they aren’t capable of doing better. Education officials instead should focus on equality in opportunities and ensure that resources go to those who need the most help (and are just as intelligent as their peers).