The average ACT score of Kansas high school students is likely to drop this year, the Wichita Eagle reports in an opinion piece. Thanks to a legislative decision last year that eliminated the $50 exam fee for some students, Suzanne Perez Tobias theorizes more students will take the test.

“But parents, elected officials, policy makers and others should be warned: As the number of test-takers increases, the state’s average ACT score will almost certainly go down,” she writes.

Ben Scafidi, a professor of economics at Kennesaw State University in Georgia, agrees additional test takers will likely mean lower average test scores.

“All else being equal, if kids are taking the ACT freely and then you lower the cost to take the test, kids who are probably less interested in going to college are probably going to take the test. Yes. That’s going to pull the average down a bit,” Scafidi says.

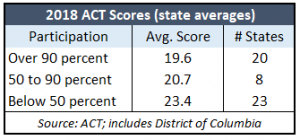

The adjacent table categorizing state average scores by participation level (as recommended by ACT) supports Scafidi’s statement. The states with more than 90 percent of student participation had the lowest average score of 19.6 last year. States with participation between 50 percent and 90 percent averaged a 20.7 score, and the highest average score of 23.4 went to states with participation below 50 percent.

The adjacent table categorizing state average scores by participation level (as recommended by ACT) supports Scafidi’s statement. The states with more than 90 percent of student participation had the lowest average score of 19.6 last year. States with participation between 50 percent and 90 percent averaged a 20.7 score, and the highest average score of 23.4 went to states with participation below 50 percent.

Perez notes that composite ACT scores have dipped the last few years. The bright spot, she writes, is that Kansas’s average composite ACT score is above the national average of 20.8. While true, Kansas has a demographic advantage that artificially increases its score.

Georgia, for example, has higher scores than on the three largest racially-based demographics, but Kansas has a higher overall score (21.6) than Georgia (21.4) because Kansas has a much higher percentage of White students and a lower ratio of minorities. The large achievement gaps between White students and minorities produces higher average scores for states with low levels of minority studetns. Texas is a full point behind Kansas on the average score, but their White students do better than Kansas (23.3 vs 22.5) and Texas’s Hispanic students only trail by three-tenths of a point and their Black students are only one-tenth of a point behind.

Only about 29 percent of those taking the ACT in Kansas last year were deemed college ready in math, reading and science. That’s slightly higher than the national average of 27 percent. In other words, less than a third of students who took the test were ready for the next level.

“Above the national average doesn’t mean much if all of the results are low,” Kansas Policy Institute President Dave Trabert.

Scafidi says the ACT is a good metric to use to determine whether students are ready for college, but they shouldn’t be used to judge education as a whole. Not every student takes the exam, and it isn’t a good indication of whether a student is career or job ready.

Adding more money to schools hasn’t increased the percentage of students who are college ready. Scafidi’s research shows that Kansas school funding increased by 39 percent in inflation adjusted spending between 1998 and 2015, and in that time ACT scores were flat.

“The experience in Kansas shows that a large increase in resources does not seem to be associated with gains of achievement,” Scafidi says.